At what age does adulthood begin in 2026?

We have to stop infantilising young people.

Reading a recent Stuff article about a 26 year old woman leading the East Cape flood response, I felt two things at once. The first was admiration. In the middle of chaos, she stepped up, coordinated people, trusted her instincts, and helped her community through a genuinely frightening weather event. That deserves recognition. But the second feeling was discomfort, not with her, but with the framing. The article treats her age as the most remarkable thing about the story, as if competent leadership at 26 is an anomaly rather than a perfectly ordinary human possibility.

What she did, although challenging, is not beyond the reasonable expectations of a 26 year old adult and I was struck by the infantilising surprise with which it was treated. The astonishment is entirely editorial, not factual. She did not succeed despite her age; she succeeded because she was allowed, in that moment, to act like an adult, to make decisions, to trust her training, and to carry responsibility without being buffered from it. The implication that this is unusual tells us less about her and more about how far we have lowered our expectations of people in their twenties.

Those plummeting expectations and the extension of adolescence is what I want to examine. Because the subtext of the piece isn’t “look what she achieved,” it’s “can you believe someone so young could do this?” And that feels odd to me. Since when did 26 become an age at which behaving like a competent and capable adult feels surprising?

For most of human history, the transition from child to adult was not particularly ambiguous. Childhood existed, of course, but it was relatively short. By their mid-teens, young people were expected to contribute meaningfully to their households and communities. They worked, married, fought wars, ran farms, managed businesses, and raised children. There was no prolonged limbo where responsibility was endlessly deferred in the name of “finding yourself.” You grew up because life required you to.

Even the idea of the “teenager” is a recent invention. The term only entered common use in the mid-20th century, emerging alongside mass secondary schooling, post-war affluence, and the creation of youth as a distinct consumer category. Adolescence stretched out because society could afford to stretch it out. What was once a brief transition became a cultural stage with its own music, fashion, attitudes, and lowered expectations.

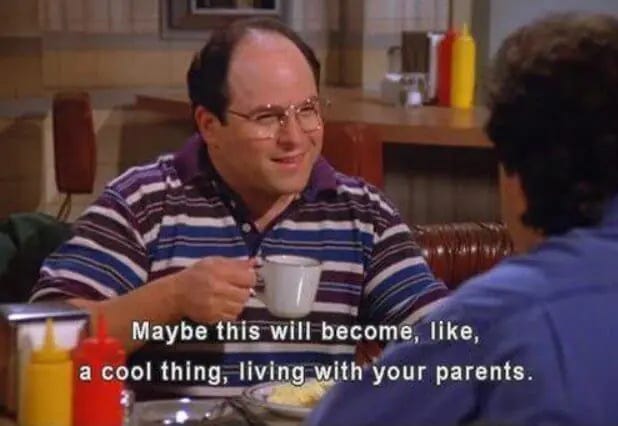

But, it appears that elongation hasn’t stopped at eighteen. Over the past one to two generations, childhood and adolescence have continued to creep upward. What used to be considered early adulthood now sits in a strange grey zone. We talk about “emerging adults,” “quarter-life crises,” and the idea that people in their mid-twenties are still basically kids, just with better phones and student debt. Responsibility is treated as something fragile, almost dangerous, to be introduced slowly, if at all.

Which brings us back to the question: at what age does adulthood begin in 2026?

If a 26 year old leading an emergency response is framed as extraordinary, then adulthood, in our cultural imagination, has drifted well past the mid-twenties. And this has consequences for individuals, for families, and for society as a whole.

It’s worth grounding this in some historical perspective. By 26, Alexander Hamilton had already been a key figure in the American Revolution. Joan of Arc was dead by 19, having led armies and altered the course of French history. Albert Einstein published his four groundbreaking 1905 papers (special relativity, photoelectric effect, Brownian motion, E=mc²) at 26. Isaac Newton developed calculus, the foundations of classical mechanics, and early optics work between the ages of 22–25. Mary Shelley wrote Frankenstein at 18, creating an entirely new literary genre. And, more recently, Mark Zuckerberg founded Facebook at 19 and by 26 was one of the most powerful figures in global communications.

Closer to home, generations of New Zealanders were married, working full time, and raising children well before that age. None of this is to romanticise the past or deny its hardships, but it does remind us that human capability has not suddenly diminished.

On a more personal level, my own parents were 26 when I was born. They weren’t anomalies either. Many of their friends had already had children or were in the process of starting a family. They were ordinary adults doing what adults did; taking responsibility for a child, a household, and a future. The idea that this same age now attracts astonishment when paired with leadership tells us we have collectively recalibrated our expectations downward.

One of the clearest markers of this shift is how long young adults now remain dependent on their parents. Living at home into one’s twenties has become normalised, often framed as a rational response to housing costs, insecure work, and student loans, all of which are real pressures. But structural challenges don’t tell the whole story. Alongside economic constraints, there has been a cultural reluctance to expect independence, resilience, or even the ability to endure discomfort from young adults.

My dad helped me write a very empty CV and apply for a job at Hell Pizza when I was 14 years old. If I recall correctly, I was paid approximately $7.50 per hour on the youth wage. Yes, in 2005 employers could pay young people less than adults. My shifts were sometimes as short as two hours, but I was expected to catch the bus (or Dad would drop me off and pick me up because it was late) and be on time. It must have felt like more trouble than it was worth for Dad, but he insisted that I was to learn the value of a dollar and the discipline that came from showing up and doing a job. I am incredibly grateful he did so, but when I tell younger people this they react in horror at a child being made to work.

We have built a narrative in which prolonged dependence is treated as protective and compassionate, rather than as something that may erode confidence and capability. When you delay the assumption of responsibility, you also delay the development of the skills that come with it like decision-making under pressure, accountability for failure, and the deep internal knowledge that you can cope when things go wrong.

There is a broader societal cost to extended adolescence too. A population that has been shielded from responsibility for too long is less resilient when crises arrive. When floods, pandemics, economic shocks, or institutional failures occur, societies rely on adults who can act without waiting for permission, validation, or emotional cushioning. Resilience isn’t innate; it’s built through experience, often uncomfortable experience. Suffering even.

I write none of this to sneer at young people or ignore the genuine difficulties they face. Housing affordability, wage stagnation, and precarious employment are real. But lowering expectations is not a solution to those problems. In fact, it may make them worse by fostering dependency and fragility rather than capability and agency.

What we are losing in this extended childhood is not some nostalgic ideal of toughness for its own sake, but a realistic pathway into adulthood. We are telling young people, implicitly and repeatedly, that they are not ready. Not ready to lead, not ready to decide, not ready to bear consequences. Then we act surprised when they hesitate, struggle, or doubt themselves.

It doesn’t just reshape how we think about adulthood. It also reshapes when, or whether, people feel ready to have children at all. If we spend our twenties being told, implicitly and explicitly, that we are not yet fully formed, not stable enough, and not ready for serious responsibility, then parenthood is inevitably pushed further and further out of reach. People wait until they feel like “real adults,” a milestone that now seems to recede into the thirties or beyond. The result is a demographic time bomb of falling birth rates, smaller families, and a narrowing window in which people can safely have children. Societies then scramble to paper over the consequences with immigration, extended working lives, and increasingly strained social systems. I know I bang on about the ageing population and the demographic crisis a lot but we should be worried. Beneath the policy fixes sits a cultural problem of our own making. By treating adulthood as something that begins later and later, we create generations who delay the most fundamental act of social renewal and then act surprised when populations age, workforces shrink, and the responsibility for generating tax to pay for overburdened social services falls on the smaller generations of young people.

I also shudder to think about what this means on a geopolitical level, when a generation raised on emotional validation, narrative framing, and hypersensitivity to discomfort becomes the one tasked with navigating an increasingly volatile world. We are cultivating a cohort that has been trained to prioritise feelings over outcomes and to interpret conflict through the language of personal offence rather than strategic reality. Set that against resilient, historically literate, and ruthlessly pragmatic leadership cultures in places like China or Russia, and we are in for a hiding to none. It is not difficult to imagine future Western leaders attempting to manage hard power conflicts with the rhetorical tools of therapy culture, objecting to an adversary’s “tone” or “vibes” while the other side calmly advances material interests. In international politics, emotional fragility is not a virtue. It is a liability, and one we are normalising at precisely the wrong moment.

What worries me most is not what young people are being protected from, but what they are being robbed of. My parents’ generation went off on OEs to the other side of the world with little more than a backpack, a paper map, and the knowledge that if something went wrong, they would have to sort it out themselves. They communicated with home by letter because international phone calls were ruinously expensive, which meant long stretches of genuine independence, no instant reassurance, no parental safety net humming in the background, and definitely no apps through which instant money transfers can be made. That distance forced competence, improvisation, and confidence into being. By contrast, many young adults today are so shielded from friction that basic adult tasks like phoning a GP and making an appointment can provoke real anxiety. If you cannot ring a doctor without emotional distress, how are you meant to navigate a foreign train system, negotiate accommodation in a language you barely speak, or recover when plans collapse halfway across Europe? Adventure requires a tolerance for uncertainty, and by smoothing away every rough edge, we are raising a generation that is missing out on the very experiences that once turned young people into adults.

The 26 year old who led the East Cape flood response should be celebrated, full stop. But the truth is that her story shouldn’t feel all that remarkable at all. It should feel normal. If it doesn’t, that tells us something important about the cultural moment we’re in and about how urgently we need to rethink what we expect of young adults, for their sake and for ours.

Exactly. And hours, days,and months playing games on computers and endlessly watching videos. Can they ever recover their misspent younger days?

When I was 14 kids could leave school at 14 and take up a full time job or apprenticeship and most did. They worked and mixed with adults, were expected to behave like adults most of the time while working and socialising

At the age of 16 they could get married and most of them did before 20 and started a family.

The reason this worked was because their life had been that of an adult for the previous 6 years and their brains had developed accordingly

The prolonged modern adolescence where ther is no real adult to adult interaction has resulted in a situation where the courts will accept that their frontal lobes are not fully mature at 26

You're right, this century is going to belong to the Asian societies that have real expectations of their children